Dendra, Argolid (1926–1927, 1937, 1939, 1960, 1962–1963)

Published: 2020-05-06

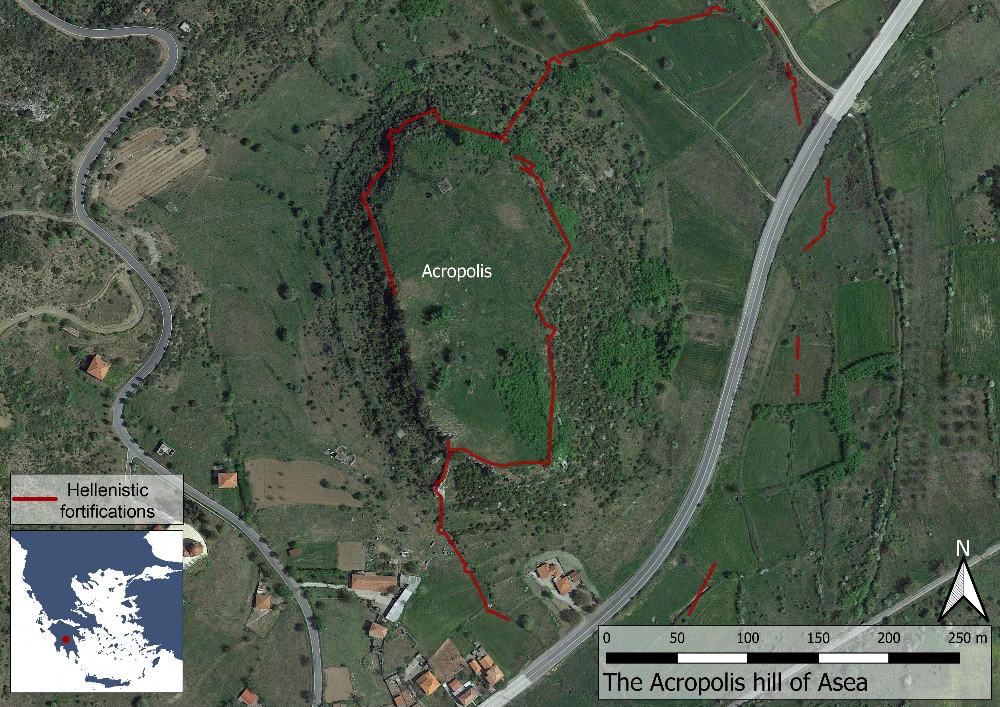

Fig. 1: Map over the site of Dendra (Basemap: Google maps satellite image).

The village of Dendra is located about six km east of the town of Argos in the Argolid. The earliest remains here are of habitation during the Early Neolithic and Early Helladic periods in the form of building foundations and scattered pottery fragments. However, the site is more important archaeologically due to its Bronze Age cemetery, consisting of a tholos, three tumuli and 16 chamber tombs. Overall, it is one of the richest Mycenean cemeteries known. Presumably it was connected to the settlement at ancient Midea, located c. 1.5 km to the south east, although most Mycenean burial places are found closer to their settlements than this.

Excavation history

The Swedish excavations at Dendra were initiated in 1926 when Axel W. Persson investigated a Mycenaean tholos tomb (Late Helladic IIIa period, c. 1450–1350 BC) at the site. At the same time several contemporary Mycenaean chamber tombs were identified. In 1927 Persson explored three of these, while the local ephor N. Bertos excavated another two. In 1937 Chamber Tomb no. 6 was excavated and in 1939 nos. 7–11. After the Second World War Paul Åström continued work at Dendra, in collaboration with the local Greek archaeological authorities, transforming the excavations into a joint Greek-Swedish project. In 1960 they made their most spectacular find as they excavated Chamber Tomb no. 12: the Dendra cuirass, now exhibited in the Nauplion Museum.

Finds

In total 16 chamber tombs, three tumuli and one tholos have been explored at Dendra, but as is often the case several of them were robbed before being excavated. Despite this the finds were impressive, leading Persson to consider the site a royal cemetery.

The three tumuli at Dendra were constructed with stone periboloi and the sparse pottery found in them suggested that they were all constructed during the Middle Helladic Period (c. 2000–1550 BC). A burnt area and hearth was found just outside of Tumulus A, suggesting activity in connection to the mound. Nearby, a tomb (no. 1) was found in Tumulus B, presumably constructed during the same period as the mound. In addition to this, three horses were buried in it during the Late Helladic III period (c. 1400–1050 BC). Another two horses from the same period were found in Tumulus C, as well as four tombs (nos. 1, 2, 15, 16) cut into the mound during the Late Helladic III period. It is thus apparent that the cemetery of Dendra was used for a prolonged period of time.

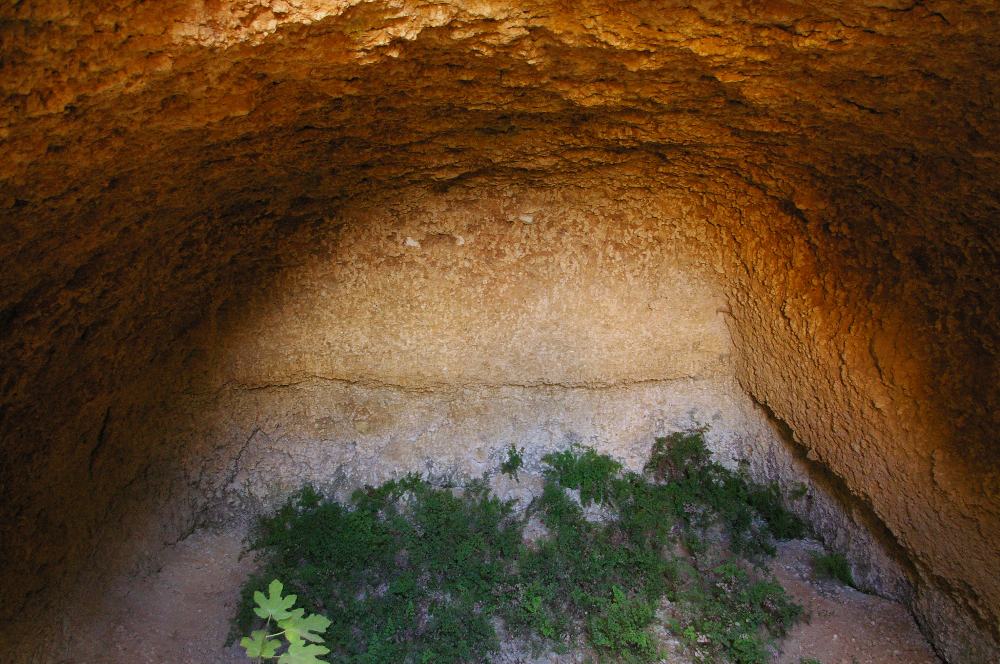

The tholos tomb which originally drew attention to the site is to be dated c. 1450–1350 BC, and located at the south-east edge of the cemetery. It consists of a vaulted chamber (tholos) with a passage (dromos) and doorway (stomion) leading to this. The dromos is 17.90 m long and 2.20–2.50 m wide, constructed of large rubble stone masonry, two to three stones thick, laid to a height of up to 5 m. When excavated, the 3.50 m tall doorway between the dromos and tholos was blocked by a rubble masonry wall. The vaulted chamber is 7.30 m wide and while not found intact, its original height can be calculated to c. 7 m.

Fig. 2: Inside the chamber of the Tholos tomb, showing the doorway.

Fig. 3: The dromos of the Tholos tomb.

Ornaments, pottery and human bones were found spread out in the tholos, stomion and dromos and four unplundered pits were identified under the floor inside the chamber. Out of these the largest contained the burial of a man and a woman along with grave offerings. These included bronze weapons, glass models of boar tusks, an ostrich egg vessel, a stone lamp, gold, silver and bronze vessels, semi-precious seal-stones as well as various ornaments of valuable materials. A woman was buried in one of the other pits, also with impressive grave goods, such as a necklace of gold rosettes, a gold ring and ornaments of faience, glass and ivory. Due to its monumentality and the rich finds it has been suggested that the tholos was constructed for a ruler of nearby Midea. After the Mycenean period the tholos itself collapsed during the earlier part of the Geometric Period (c. 1050–700 BC). Following this a secondary burial was placed in the blocking wall at some point during the 9th century BC.

The chamber tombs also yielded significant information. Particularly important finds were made in no. 12, c. dating to the end of the 15th century BC. The tomb itself was formed of a roughly rectangular chamber with rounded sides. Instead of the usual dromos, a shaft was used to access the chamber. Unfortunately, the tomb was partly looted shortly before the excavations, with robbers removing some of the finds and disturbing the single male burial. Yet, the unlooted parts of the tomb contained spectacular discoveries. The most impressive was a unique bronze cuirass, today exhibited at the museum in Nafplio. In addition to this the archaeologists found items such as weapons and silver cups.

Chamber Tomb no. 16 is also of interest because it exemplifies the interaction between older and more recent monuments at the site. As most of the other chamber tombs, no. 16 was constructed with a long sloping dromos leading to a monumental façade. The chamber itself was a crude rectangle with a gabled roof and plastered walls (now collapsed). Originally the opening to the tomb was blocked by a rubble masonry wall. In the tomb neither primary nor secondary burials were located. Instead a small number of clay vases as well as scattered bones were found, along with traces of intense fire, perhaps testifying to ritual practices. Importantly, when constructed Chamber Tomb no. 16 partly destroyed the much older Tumulus C. In order to rectify this the upper part of the tomb’s façade was lined with flat stones. This suggests that although the older tumuli were repeatedly damaged during later periods, they were not completely disregarded.

Fig. 4: The inside of Chamber tomb 16.

The Late Myceneans horse burials at Dendra are also notable. Among these, three complete bodies were excavated in the Middle Helladic Tumulus B. These horses were all male, 14–17 years old and placed in shallow pits or directly on the bedrock in different positions. No cause of death could be established but it is considered likely that the animals were sacrificed. A few meters away, the dismembered remains of another three or four horses were located. Presumably this represents a secondary burial after the decomposition of the bodies. This interpretation suggests reoccurring sacrifices of horses at Dendra. This is significant as these valuable animals constituted impressive victims, signifying the status of the owner as well as the site.

Fig. 5: The horse burials in Tumulus B.

Bibliography

Åström, P. 1967. ’Das Panzergrab von Dendra: Bauweise und Keramik’, AM 92, 54–67.

Åström, P. 1977. The Cuirass Tomb and other finds at Dendra I: the chamber tombs (SIMA 4), Göteborg.

Åström, P. 1983. The Cuirass Tomb and other finds at Dendra II: excavations in the cemeteries, the Lower Town and the Citadel (SIMA IV), Göteborg.

Hägg, R. 1962. ‘Research at Dendra 1961’, OpAth 4, 74–102.

Persson, A.W. 1931. The royal tombs at Dendra near Midea (Skrifter utgivna av Kungl. Humanistiska vetenskapssamfundet i Lund, 15), Lund.

Persson, A.W. 1942. New tombs at Dendra near Midea (Skrifter utgivna av Kungl. Humanistiska vetenskapssamfundet i Lund, 34), Lund.

Schallin, A.-L. 2006. ‘Identities and “precious” commodities at Midea and Dendra in the Mycenaean Argolid’, in Local and global perspectives on mobility in the eastern Mediterranean (Papers and monographs from the Norwegian institute at Athens, 5), ed. O.C. Aslaksen, 159–190, Athens.

Verdelis, N. 1967. ‘Neue Funde von Dendra’, AM 92, 1–54.

Wells, B. 1990. ‘Death at Dendra: on mortuary practices in a Mycenaean community’, in Celebrations of death and divinity in the Bronze Age Argolid. Proceedings of the Sixth International Symposium at the Swedish Institute at Athens, 11-13 June, 1988 (Skrifter utgivna av Svenska institutet i Athen, 4°, 40), ed. R. Hägg & G. C. Nordquist, 125-140, Stockholm.