Hermione, The Argolid (2015- ongoing)

Published: 2021-02-10

Fig. 1: Map over Hermione (Basemap: Google maps satellite image).

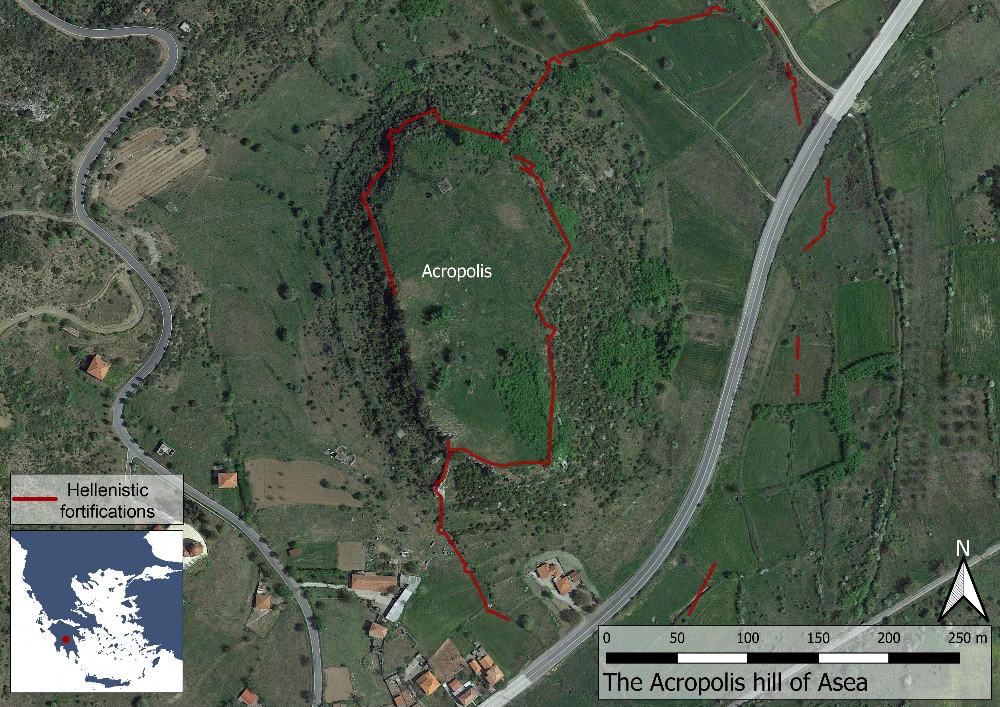

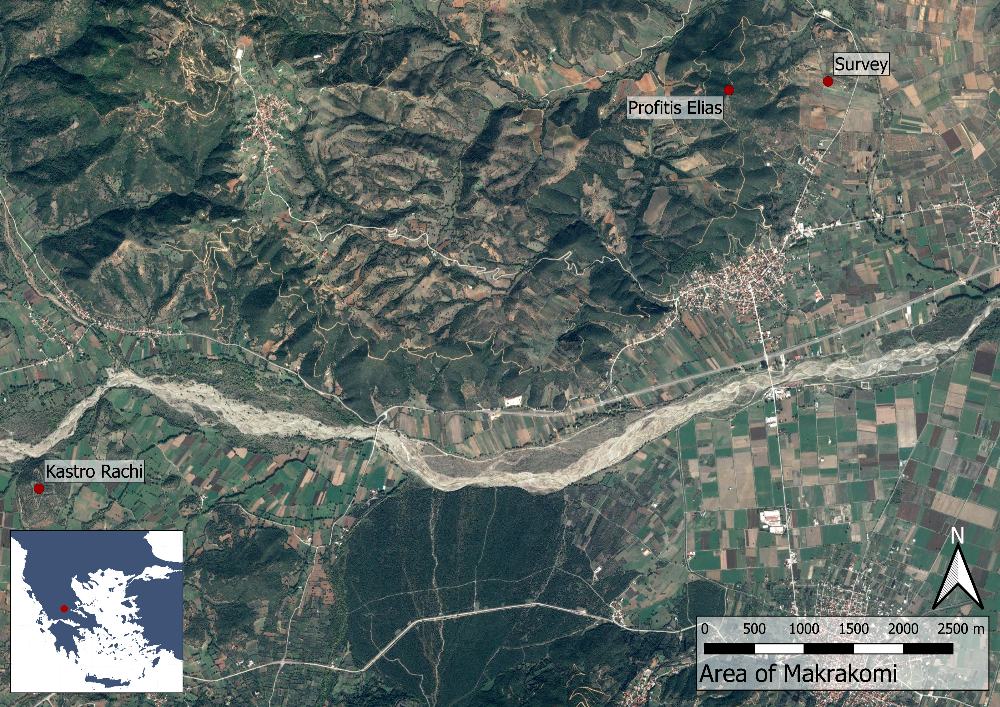

Ancient Hermione was one of the city states of the southern Argolis region. Today the remains of the polis mostly lie under the homonymous modern town, located on a long narrow peninsula. Its tip, known as the Bisti, is a park, whereas today’s Hermione covers the east slope of the 70-meter tall Pron hill. A fertile plain, once hosting a water course, is found between the Pron and the mountainous Peloponnesian landscape in the north. Both sides of the Hermione peninsula feature excellent natural harbours.

The polis of the Hermionians has a long history. It is first mentioned in Homer as one of the cities under Diomedes’ leadership (Il. 2.560). While there is no evidence of pre-historic habitation in the area of the modern city, remains from the Mycenaean period have been found on a hill located about a km to the east. In the area of ancient Hermione early testimonies come from Proto-Geometric tombs. Literary sources note that the Hermionians sent ships to Salamis and men to Plataia during the Persian Wars in the late Archaic period, when we know that the city was located on the Bisti tip of the Hermione peninsula. At some point, probably between the mid-Hellenistic and Early Roman periods, and for unknown reasons, the city was moved 800 m to the west and relocated to the east slope of the Pron. Pausanias, who visited the city in the 2nd century AD, provides an unusually rich testimony as he found the city a place “which afforded much to write about” (Paus. 2.34.11). Archaeological evidence from the Roman periods further corroborates the notion that the city flourished in the Imperial era. In later Christian times Hermione became a bishopric with a large basilica, remaining inhabited at least until the 6th century AD.

In 2015, the Ephorate of Antiquities of the Argolid and the Swedish Institute at Athens initiated a joint three-year study of Hermione called A Greek cityscape and its people. A study of Ancient Hermione. The General Director of the project is Dr. Alcestis Papadimitriou, Ephor of Antiquities of the Argolid, while Dr. Jenny Wallensten is responsible for the Swedish team. The study of ancient Hermione continues since 2018 through the current research program Hermione: A model city. The projects aim to create a better understanding of life in a Greek polis from a long-term perspective through integrated studies of the built environment, landscape, family and other social structures as well as religious practices, including funerary rituals.

Fig. 2: Overview of modern Hermione with the Bisti in the distance.

Ancient remains in Hermione

Exploring Hermione, the Greek-Swedish projects have employed non-destructive approaches as far as possible, including digital and traditional documentation methods for visible remains, various types of geophysical survey, and analysis of the present landscape. This has enabled a large number of studies to be performed, rapidly expanding our knowledge of the ancient city, almost without excavations.

The earliest city, dating from the Archaic period, was located on the Bisti, where remains include the foundations of the temple of Poseidon or Athena, stretches of the Classical city walls, a so-called Venetian wall as well as more than a dozen cisterns.

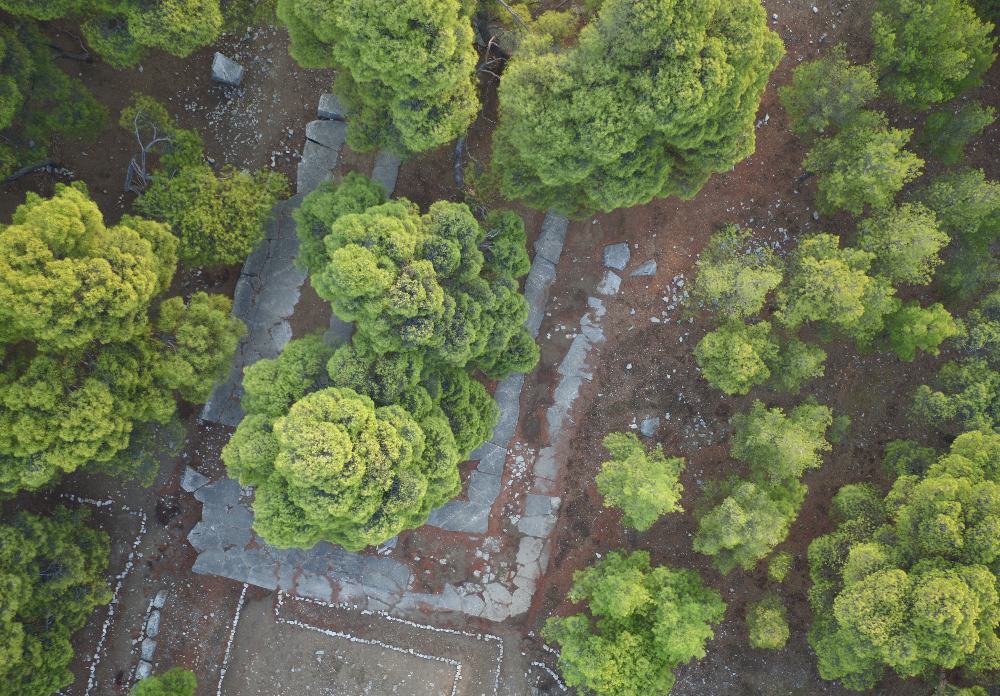

The Late Archaic–Early Classical temple, mentioned by Pausanias (2.34.10), is located at the highest point of the Bisti, giving it a prominent position in the landscape, overlooking the sea. Today only the foundation, measuring about 15×30 m, can be seen. The ancient temple was destroyed long before modern times and a medieval church, of which faint traces can still be seen, was built on top of it.

Fig. 3: The foundations of the temple of Poseidon on the Bisti.

There are also substantial remains of fortifications on the Bisti. The oldest are city walls dating to the Classical or Hellenistic period, following the edge of the peninsula. These fortifications were later rebuilt in Medieval times, resulting in a mix of building techniques. The most substantial preserved fortifications are, however, the c. 3 m thick so-called Venetian wall (14th–16th century AD), cutting off the Bisti from the rest of the peninsula. This wall was largely constructed using older material as evidenced through the large number of inscriptions and architectural blocks visible in it.

Domestic habitation from the Classical and Hellenistic period on the Bisti is primarily testified by the cisterns spread over the area. These are of a common bell- or pear-shaped type with a volume of 10–30 m3, enough to supply a family with water throughout the year. Their location in the landscape is significant as cisterns were used almost exclusively in domestic contexts. Consequently, they can be used to trace public and private spaces in the ancient city.

Throughout the project the landscape of the Bisti peninsula has also been analysed in order to locate terracing and to identify further remains of ancient structures, including rows of houses. Concurrently several different geophysical survey methods have been used in order to explore remains below the surface. In 2019 two small test trenches were opened in order to better understand the results of these efforts without further extensive excavations.

Fig. 4: The Agioi Taxiarches church with visible spolia.

There are also many traces of ancient Hermione in the modern city, ranging from single architectural elements and inscriptions incorporated in recent structures to foundations and huge walls. The temple of Demeter Chthonia is the most significant identified structure. It lay in a sanctuary described by Pausanias in the 2nd century AD as “the object most worthy of mention” (2.35.4) and located on a highpoint in the terrain. The cult itself is attested from the 6th century BC, and much later Pausanias described a particularly unusual ritual where cows were led into the temple and killed by old women with sickles (2.35.6–7). Originally the shrine may have been an extra-urban sanctuary, when the city was still located at the tip of the peninsula. Later, as the town moved to the Pron, the shrine was incorporated in the urban landscape. The remains of the temple are preserved under the Agioi Taxiarches church which also incorporate many spoila, from the temple as well as other structures, in its walls. Some 70 meters to the north of the temple, 40 meter of a monumental retaining wall is preserved up to a height of almost four meters. This wall may have marked the extent of the temenos, but no further evidence is currently available.

Closer to the Bisti a three-isled basilica from the 5th century AD with later modifications is located. The building was excavated already in the 1950s by Eustathios Stikas who found several well-preserved mosaics. It has been hypothesized that an adjoining structure was the bishop’s palace. The size and decoration of the structures testify to the prosperity of Hermione during the period.

At the east end of modern Hermione, close to where the Pron hill rises sharply, an 18-meter stretch of polygonal fortification wall is visible. This was presumably part of the Classical-Hellenistic fortifications of the city and served as a foundation for the wall proper and perhaps a ramp leading up to a gate. Beyond this gate the extra-urban area of Hermione began with an ancient road leading out of the city following the north foot of the Pron hill. Today remains of this road, the city’s necropolis and a 2nd century AD Roman aqueduct have been identified. The latter is three km long with a calculated daily output of about 500 m3, making it small in comparison with other contemporary aqueducts on the Peloponnese. Yet, for a city the size of Roman Hermione it would have represented a considerable and much valued contribution to the water supply.

Fig. 5: Section of the Roman aqueduct of Hermione.