Makrakomi, Phthiotis (2010–2015)

2020-06-02

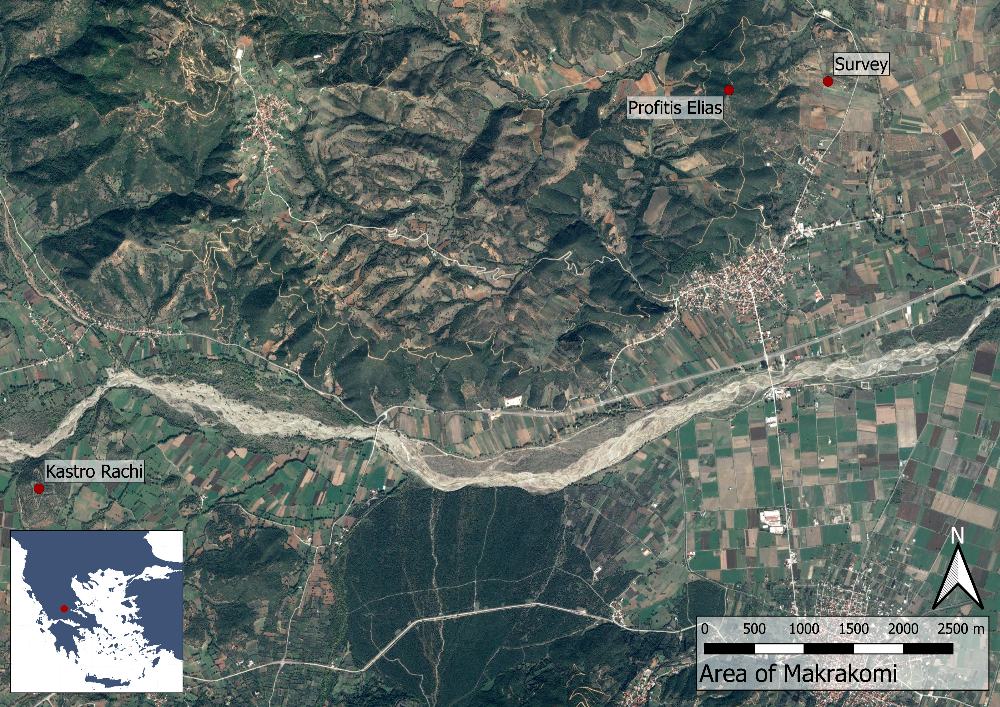

Between 2010 and 2015 the Makrakomi Archaeological Landscapes Project (MALP) conducted fieldwork around the village of Makrakomi in the Spercheios valley, located in the western part of Phthiotis (central Greece). Limited by tall mountains in the south, north and west, the valley and its homonymous river stretches towards the Malian gulf in the east. Due to its position, the valley has acted as a border zone between northern and southern Greece, as well as a natural passage for both armies and travellers. This made the valley increasingly important during the Late Classical and Hellenistic periods as armies marched across Greece more frequently following the rise of Macedonia.

Fig. 2: The Spercheios river during summer, photographed from the hill of Kastrorachi.

Fieldwork history

Until recently only little archaeological work had been conducted in the western Spercheios valley, with the exception of historical-topographical studies in the early 20th century by scholars such as I. Vortsela, F. Stählin and Y. Βéquignon. This lacuna can largely be attributed to limited modern construction in the area, minimizing the need for rescue excavations, and a scholarly focus on other areas of Greece. Aiming to achieve a better understanding of antiquity in the valley the Archaeological Ephorate of Phthiotida and Evrytania, under the direction of Maria-Foteini Papakonstantinou, in cooperation with Swedish archeologist Anton Bonnier, therefore initiated the Makrakomi Archaeological Landscapes Project (MALP) in 2010.

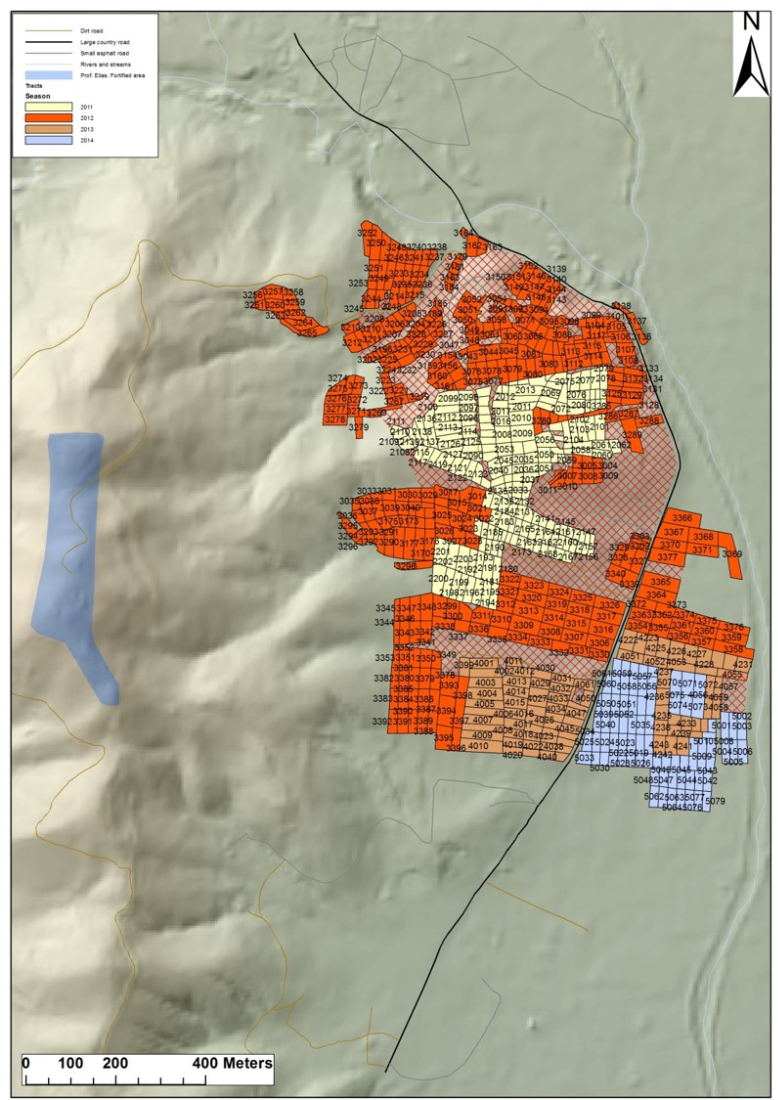

Fig. 3: Areas surveyed at Profitis Elias and Asteria.

During the first season (2010) a pilot survey was conducted in and around the Profitis Elias hill with its extensive remains of ancient fortifications. In 2011 systematic investigations began within the framework of a five-year project which included surveys, geophysical investigations (covering more 22.0000 m2), small scale excavations and geomorphological studies. During 2011–2012 an archaeological and architectural survey was performed, recoding traces of an ancient settlement at Asteria. A small number of test trenches were also opened in the same area in 2012 in order to better understand the geophysical results. In 2013 work was expanded to include the site of Kastrorachi some 8 km southwest of Profitis Elias, with the aim to investigate the density of surface artifacts inside and outside of the ancient fortifications. During 2014 work continued at Asteria, including further architectural survey. The last field season of MALP took place in 2015 with the re-surveying of several areas in order to test the methods used during the project and collect a reference collection for further analysis.

Fig. 4: Field walking during the project.

History

The earliest known habitation in the Spercheios valley dates to the Neolithic period (6500–3300/3000 BC) and human presence is attested throughout the Bronze Age (c. 3000–1070 BC) with a peak during the Middle (2000–1600 BC) and Late Helladic (1600–1070 BC) periods. However, prehistoric finds are sparse and there is no indication of long-lived settlements before the Late Classical period (400–323 BC), although, according to tradition, the valley belonged to the kingdom of Achilles during the end of the Bronze Age.

The Spercheios valley of historical times is mentioned only sporadically in the ancient textual evidence, leaving archaeology as our main sources of information. Herodotos (7.198.2) and Thucydides (5.51.1–2), however, noted that the area was inhabited by three distinct ethne, ethnic communities, the Oitaioi, the Malians and the Ainians. From the late 5th century BC the valley and its inhabitants lay within Thessaly’s sphere of influence. During the late 4th and early 3rd century BC settlements and land use in the Spercheios valley expanded rapidly. At this time the twin summits of the Profitis Elias hill, possible identifiable as the Ainian settlement of Makra Kome, were fortified with strong trapezoidal walls and numerous towers; Βéquignon identified a possible gate in the west already in the 1920s. It also seems clear that a settlement, datable to the same period as the fortifications, was laid out just east of the hill in the area known as Asteria, where a dense scatter of pottery reveals the presence of habitation during the Late Classical and Hellenistic period. Finds also included fragments of a Doric column or pilaster, remains of several Olynthian mills, various kinds of lamps as well as two Hellenistic coins. Overall the material gives the impression of a primarily domestic habitation. This is corroborated by a lack of evidence for monumental structures, with one potential exception of unknown nature. Geophysical surveys revealed that the settlement was unwalled but well-planned following a north-south and east-west oriented street grid. A small excavation in the central area of the settlement located the remains of a domestic structure dating to the Late Classical and Hellenistic period (House A). This was constructed with stone foundations which presumably supported a mudbrick superstructure. To the north and the west of House A the surfaces of two roads, covered by tile fragments and pottery sherds, were uncovered.

At around 300 BC a large number of sites were fortified, including that at Profitis Elias, in the Spercheios valley, for example at Ano Fteri, Palaiokastro-Dikastro, and Rovoliario. These fortifications remained in use until Roman times and testifies to major investments in defensive systems at the time, by both the Ainians and Malians. The fortification at Kastrorachi was investigated within MALP, with campaigns identifying material from the late 4th century BC to the 2nd century BC both inside and outside of the walls. This suggest that the fortress was largely contemporary with the habitation at Asteria.

![Fig. 5: Tetradrachm found during the survey depicting Herakles/Alexander the Great in a lion skin on the obverse and a seated Zeus holding an eagle and a scepter with an inscription reading ΑΛΕΧΑΝΔΡΟ[Υ] (Alexander’s) on the reverse.](../images/research/makrakomi_fig.5.jpg)

Fig. 5: Tetradrachm found during the survey depicting Herakles/Alexander the Great in a lion skin on the obverse and a seated Zeus holding an eagle and a scepter with an inscription reading ΑΛΕΧΑΝΔΡΟ[Υ] (Alexander’s) on the reverse.

During the 3rd century BC the Ainians joined the Aitolian League, a loosely organized group in north-western Greece, presumably in order to further increase security in a world now dominated by large kingdoms rather than small city-states. They remained within the league until around 150 BC, although it had become all but irrelevant already in 189 BC when the Romans turned the member states of the Aitolian League into subject allies.

Little is known about the Spercheios valley during Roman times. Overall the archaeological sources paint a picture of little activity. The old fortification systems were abandoned, although there is some identified material dating to c. 100 BC–200 AD at Profitis Elias. At Asteria the limited number of sherds suggests that the site was much contracted, if inhabited at all, during the period. The complete lack of material at Kastrorachi indicates that it had been abandoned. It therefore seems that, as in many other areas of Greece, the urban centres in the Spercheios valley could not be sustained under the new Roman political structure. Post-Roman period material seems largely absent in the areas surveyed, with only a small number of possibly Medieval and Early Modern sherds found in the southern part of the area of Asteria.

Bibliography

Papakonstantinou, M.-F., A. Penttinen, G.N. Tsokas, P.I. Tsourlos, A. Stampolidis, I. Fikos, G. Tassis, K. Psarogianni, L. Stavrogiannis, A. Bonnier, M. Nilsson & H. Boman 2013. ‘The Makrakomi Archaeological Landscapes Project (MALP). A preliminary report on investigations carried out in 2010–2012’, OpAthRom 6, 211–260.

Fig. 1: Map over the site of Makrakomi (Basemap: Google maps satellite image).

Printed: 2026-03-14

From the web page: Swedish Institute at Athens

https://www.sia.gr/en/sx_PrintPage.php?tid=340